Nostalgia in Fashion

Nostalgia has been the driving force of our culture for… ever maybe, but hasn’t it felt recently that the past is collapsing in on itself?

I detest the way that nostalgia has taken over fashion discourse on all corners of the internet. It is impossible to discuss the latest viral-bait low-effort Balenciaga streetwear replica without ten people piping up to say “If Cristobal saw the state of his house today, he would roll over in his grave!” etc etc in ad infinitum ways to express the same sentiment: Things were better in the past! Balenciaga was better in the 20s or 40s or 60s or whatever random mythologized era commenters choose to idolize that they may or may not know anything about

I think this take originated somewhere in 2018 and people have been repeating it ever since… so tired!!!

I feel like I am going insane—just walking through a funhouse with the same take refracted and regurgitated a million different ways by people who are waiting for their tastes to be shaped through hindsight.

Nostalgia is just too easy, it’s safe, it’s comforting. Naturally, people paste over bad feelings they have about events now when looking back on them in the future, but it can also make you fixate on things in the past. It makes the highs of your life positively alpine, and the lows become neutral or even good events, and instead of being able to look back at your ups and downs, everything feels like an up. And this is a feeling that has consumed our culture and eaten away at our ability to live in and celebrate the present.

Consider this: the high school track and field or football star who still lives in your hometown. He is always talking about the ‘good old days’, hanging out in the same spots you did as teenagers, and probably trolling the hell out of local tinder. He is nostalgic for a time when everyone cared about him and what he did, and, through the analgesic fog of nostalgia, has only now become the prime of his life. We would all say, with great derision, that this man ‘peaked’ in high school.

Nostalgia is just too easy, it’s safe, it’s comforting.

So why is everyone trying their damndest to insinuate that Fashion—essentially the entire concept—peaked at some point in the past, and we are all living in some culturally stagnant present that exists at the end of history?

Let’s talk about nostalgia in fashion and how our culture is creating an unconscious amalgam of everything between the year 1995 and 2012.

Quickly, trends are popular items, themes, and motifs, that are In Fashion. What does it mean to be In or Out of fashion? Who knows. All I can think about is A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Ersatz Elevator where the villainous and distantly related aunt, Esmé Squalor, who lives in a penthouse in New York City is obsessed with all things fashionable and especially what is In or Out (we can talk about sexist depictions of vapid and evil yet ‘dumb’ women in media, but that is another conversation for another day). Who decides these trends? You can go down the rabbit-hole yourself of high and low fashion, but, in general, trends are things that ‘everyone’ likes for the moment, but may think is tacky next year or next season.

I understand trends in the same way I understand the stock market: we all convinced ourselves that this is reality and then it became true. Why? They’re cultural tulpas, and, when I accepted that, it all made sense. It is a fact of life that we are neither above nor removed from. I learned to love the bomb. I am the bomb. We are the bomb.

Now, think about the clothes you wear now, things you have bought in the past 4 to 8 months, and why you bought them. Did see something on someone else, in real life or in an ad and thought to yourself ‘that’s cute’ or did you see a few videos on TikTok or Instagram about the newest freshest trends that will be taking the youth by storm in a few months? And were those trends actually new or something we saw taking place a decade ago or more?

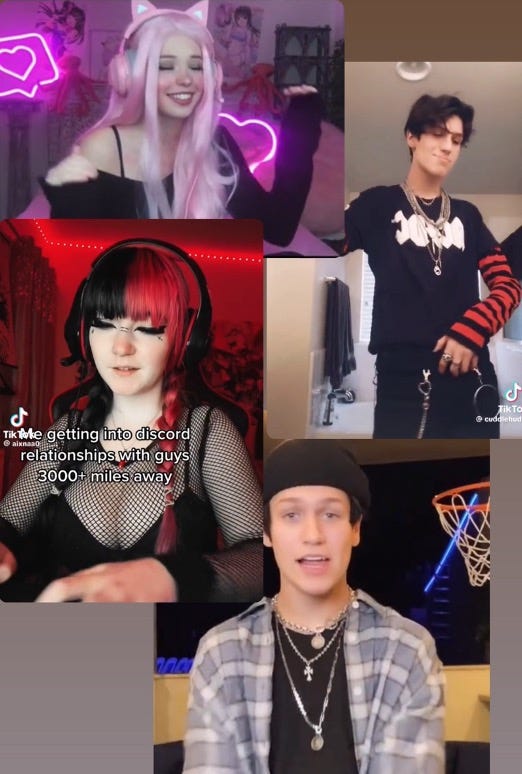

There is a commonly cited rule that trends will come back around two decades after originating. It’s the 20-year cycle, meaning that is almost inevitable for the fashions of the late 90s to come back into style in the early 2020s. Consider the y2k ‘aesthetic’—a collection of trends and styles—how you first encountered it, and how it has changed from 2018 to 2024. What was interesting about the resurgence of the late 90s fashion as it has been popularized through social media, was that it occurred in reaction to an inflection point in our current a wave of trends originating almost exclusively from TikTok: the E-Girl/E-Boy. For simplicity I will refer to it as the E-aesthetic or E-teens going forward yet you should be aware that these were distinct and gendered movements as well.

Only the tackiest of subcultures can survive in the modern day.

The E-aesthetic was the peak of late 2010s fashion and streetwear refracted through teenagers that might have just caught the tail end of Tumblr, emo internet micro-celebrities, and the hype-beast craze.

What did the E stand for? Emo, electronic, e-nternet, or perhaps nothing? It was the start of the current wave of vapid counter culture where the only thing characterizing someone standing against the mainstream is how they dress, and not how they think. The E-kids were intensely modern in the way that they were only referencing the past as a starting point to build out the rest of the counterculture aesthetic. If they were truly nostalgic for anything, it was only for the price of Hot Topic jeans being $20.

The E-teens were wearing tight ripped skinnies (like a late aughts emo) over ripped fishnets (late 2010s Tumblr goth or perhaps true 80s goth), layering boxy tees over striped shirts (as if to hide non-existent self-harm scars in 2010s emo fashion), mixing colorful flannel patterns (2010s hype beast), chains (emo/goth), skater skirts and harnesses (so very Tumblr). The makeup was over-the-top in a way that only looks gorgeous when seen through airbrushed beauty filters—the hair was black, flouncy, disheveled and optionally split-dyed with vibrant colors that could only be found in the nuclear fallout of Manic Panic box dyes of the late 2000s. And, finally, the shoe of choice were checkered converses.

They were not irreverent of their past emo legacy, but not slavishly dedicated to recreating it either, and unafraid to participate in some of the worse environmental practices in the name of fashion by purchasing their clothes through internet-only retail marketplace AliExpress—or perhaps Amazon. Brands were not the name of the game, especially if dupes or fakes could be easily purchased through the aforementioned mentioned platforms. So deeply entrenched in—yet ignorant of—internet culture that it could only be fomented on the newest social media platform around at the time of its emergence: TikTok. It was beautiful, and it was disgusting. Hundreds of thousands of teens bought in to the perfect modern expression of excess and decadence in a trend that would be over in a matter of months.

It was, by definition, a flash in the pan that served to catalyze a massive reaction in mainstream fashion. No big fashion houses put out E-aesthetic collections or appropriate the movement like they did at the peak of streetwear (see: Appointing of streetwear legend Virgil Abloh to be creative director of Louis Vuitton). It was the complete antithesis of all the trends that had begun to pick up steam around 2019 and would later take over in the 2020s.

The E-aesthetic became a reference point for all of the things that we were trying to move away from in the late 2010s. It was a mirror held up to popular culture and the overwhelming response was to turn away. We wanted to look for something ‘better’—something perhaps purer and more authentic. These are traits that only really shine through the lens of nostalgia, and, combined with the collective trauma of the COVID19 pandemic, people were looking to live in any time but the present. Then, right on time, the y2k aesthetic emerges as a dominant force in fashion.

I just wanna go back to 1999, says Charli XCX and Troye Sivan in their underground hit single 1999 (released in 2019, but they were y2k early adopters, so it only makes sense). Bluemarine Spring/Summer RTW 2023

Both fashion and nostalgia are reactionary forces. Trends occur in reaction to what is happening in fashion currently, and nostalgia is a yearning we retreat into when the present becomes too alienating. Therefore, it makes sense that fashion runs in cycles of nostalgia—when the present is too hard to live through, people would rather know how ‘It’ all plays out, and with all the trends laid out for us.

When we—people under 18 at the time—were exposed to the E-kids, we felt a bit more hopeless for the future that was predicted in our present—whether we were consciously aware of it or not. Our modern problems like health, fast fashion, overconsumption, inflation, pollution, and global warming are overwhelming, yet there are no simple and easy solutions because we all have a role to play in building a better future. The uncertainty and anxiety that we experience is driving a great wave of nostalgia and longing for the good-old-days everywhere.

Yet, our clothes are one of the only things that we—each individual person—exerts almost complete control over. It is a way to take power back from the forces that be that dictate our economy and politics. Some relish in that control, and other relish in the lack of control by surrendering totally to the mainstream to fit-in. Either way, it is a choice, and both choices can be informed by nostalgia

So, when people started looking backwards again, we receded to a time period that was equally tumultuous but also a period where we can retroactively see that things went just fine into the future: The early 2000s, but under the brand-friendly title ‘y2k,’ all lowercase.

[Fashion] is a way to take power back from the forces that be that dictate our economy and politics.

Now, 90s nostalgia is nothing new. I certainly remember during the streetwear days seeing old logos plastered, or, rather, heat transferred, onto the front of hoodies to signal to people that you were a 90s Baby™. However, this current wave is somehow far less abstracted than logos on tees—it is all about direct copies, references, or callbacks to the styles and trends of the late 90s and early 2000s while also expanding the definition and time period of y2k to flatten an entire decade or more into easily digestible trends. And this time, major fashion houses took notice.

Since 2020 we have been inundated with runway callbacks to the early 2000s (and note the shift of time frame from pre- to post- year 2000) from labels looking for re-introduce themselves into the younger market by taking advantage of their archive. Is self-plagiarism still plagiarism? A few examples: Diesel Pre-Fall ‘22 (remember the skirt that you couldn’t sit down in), Blumarine Fall/Winter ‘21, DSQUARED2 Fall/Winter ‘21, Anna Sui Fall/Winter ‘21. Nowadays, nostalgia is a safe way to make money.

Anna Sui doing the 90s-Does-70s in 1992 and then 20s-does-90s in 2020 via referencing herself… can you tell which is which?

Here is a case study that demonstrates how betting on nostalgia can be used to totally rescue a brand as well: After being ‘cancelled’ in 2021 over a distasteful photography shoot where kids were posed next to explicit documents in a post-PizzaGate world, Balenciaga wiped its social media pages and went on a full nostalgia trip. Their Instagram account began posting videos showcasing original Cristobal Balenciaga couture pieces and speaking to the legacy of the brand. It was pure Retvrn schlock with a high fashion skin because they were trying to make their customers remember what Balenciaga is all about—selling beautiful clothes—by returning to an era when that was seemingly all they did. Then for the next two or three seasons they showcased numerous pieces referencing the earlier decades of the house under Cristóbal Balenciaga and kept celebrity appearances to a minimum. Then, probably after seeing recovering sales, they promptly switched back to doing what Denma actually wants to do: make Balenciaga into a Vetements diffusion brand /j.

The boundary pushing nature of Denma’s Balenciaga was shoved aside in an effort to restore their reputation in the eyes of the public. The couture was still edgy, but in a way that was easily readable to be referencing their archive. It was a smart play at the time too because consumers, media, and fans alike loved it. So, finances and reputation now recovered, they have gone back to being the usual irreverent Balenciaga releasing $3,000 tape bracelets, and social media watchers have gone back to making their vapid and useless comments—and I don’t even like Balenciaga because I think the whole irony thing has been tired since at least 2020.

On the other hand, houses and brands like Blumarine and Diesel are instead repackaging nostalgia into ‘challenging’ collections because it is still reactionary to what is happening now and thus edgy.

This all then leaves the question: what is happening now, other than simple nostalgia?

Have you noticed that trends—and life—have been getting really meta lately? The highest grossing R-rated movie in American history, recently surpassing the Christian-cycle-play-as-movie The Passion of Christ, is Deadpool 3. A movie that loves to play fast and loose with audience and fan participation and the fourth wall. Now the fashion loving public might be a little less MCU and a lot more Wong-Kar Wai, supposedly, but it all points to the mainstream adoption of meta more-informed-than-thou attitudes that has led to the breakthrough of trend forecasting as trend-within-trend.

Trend forecasting itself emerged as a craze in late 2021 and 2022 with actual Trend Forecasting Consultant and fashion writer Mandy Lee (AKA oldloserinbrooklyn) going viral on TikTok for allowing the casual fashionista to have a peek at what goes on ‘behind the scenes’ at allllll the major or notable fashion houses—or at least letting us think that. She is the fashion consumers Deadpool (or maybe Fleabag), if you will, poking holes in the fourth wall and letting us know what fashion houses, big and small, believe they can make popular with the general and/or high fashion consuming public. Like I said before, our current y2k chasing nostalgia is an effort to see where we cannot see—into the future—and that is squarely where trend forecasting fits in.

Have you noticed that trends—and life—have been getting really meta lately?

You, the audience, are given a false sense of power by certain influencers and writers giving you a seemingly stripped back man-behind-the-curtain look at the fashion industry and what people are going to tell you is trendy and therefore the trends. But truthfully, there is a large gap between what people sell us, what we buy, and what becomes trendy. Trend-forecasting is just another way to try and recapture and democratize cultural power from fashion houses by letting us appear to pick and choose what we want to wear to be trendy—our ‘personal style.’

A selection of Mandy Lee’s content.

What’s more, people are beginning to retroactively cast trends for us to choose to adopt into our identity, like the recently dubbed Shoe Diva aesthetic cobbled together from an art trend in the mid-2000s and now repackaged into a coherent an understandable category label for you to pull from at your choosing. The Consumer Aesthetic Research Institute, founded in 2019, is another symptom of this categorization that is easily accessible for the influencing/influenced public to select from through the Institutes public facing pages and the diffusion of its consumer research through the even more freely available Aesthetics Wiki. Most of their categorized ‘aesthetics’ are entirely retrospective and did not have a name at all at the time, or if the style movements were named, they were not names and categories available to the general public. If you can cast your mind back to the halcyon days of 2012, you may remember that the word ‘Hipster’ was applied to about every other subculture that wasn’t emo. No one said ‘Indie-Sleaze’ or ‘Twee’, and anyone from Taylor Swift to The Cobra Snake were called Hipsters.

We are trying desperately to telegraph all of these movements as if we can pick and choose what to make ‘happen’ because, through the internet, we’ve been given a great amount of power over trending topics and conversations. However, I still believe that, even with the overwhelming presence of social media in all of our lives, overarching years-long trends are mostly still fomented by in-person contact or by fashion labels and celebrities in combination with economic and cultural forces.

Bringing this back to y2k, the definition, clothes, and aesthetics of this aesthetic has been expanding and stretching over the course of this article and the last 10 years to not only encompass the years 1995-2005, but has begun to include the late 2000s and even all the way to 2012. Why? Because the actual nostalgic fashions being referenced by fashion houses have been movie while we, the public, are fixated on the one term—the trends have changed and we have simply labelled all trendy and nostalgic things ‘y2k’ in the same way we slapped the word Hipster onto everyone post-y2k.

Only now, through the internet, can we be given any sense of power over the trends and fashions that can have quite a lot of influence over our lives through how we are perceived, categorized, and treated. This is a false sense because, in reality, I believe that we’re searching for a kind of comfort that cannot be provided by trend-forecasters, nostalgia, or personal style. We are using labels and aesthetics to attempt to neatly categorize our trends and nostalgia so that we can know exactly what we want and all the pieces to put together a perfect y2k tolerance of uncertainty and crisis. We’re moving at an unrelenting pace into the future and resisting it by moving backwards through the present. We are stuck in Fashion Tenet and none of us are the protagonist.